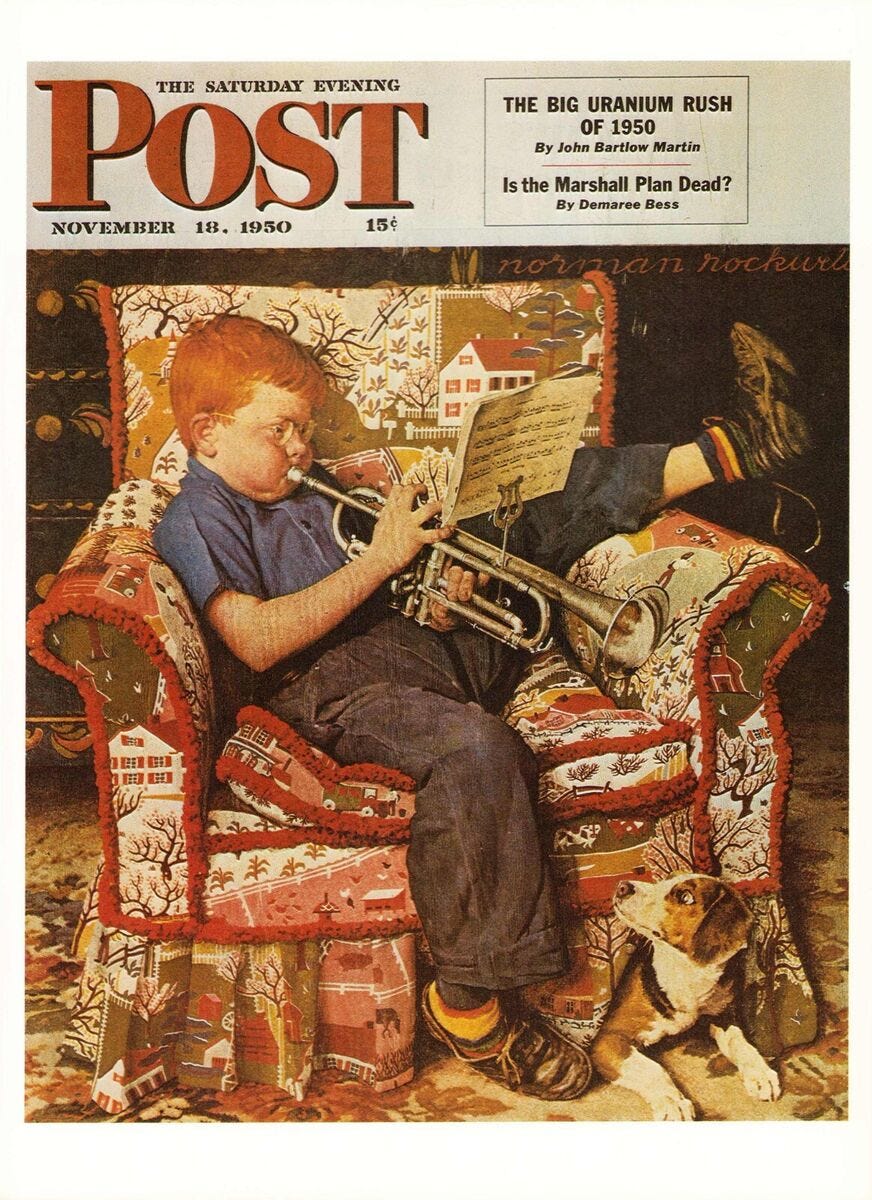

About Practice

From 6th grade through high school, I spent a good chunk of time playing the Viola. It wasn’t the coolest instrument, but I liked it. Childhood me picked it because it was like the violin, just less squeaky. I wanted to play the drums too but I didn’t have enough elective slots (I was already juggling tennis and learning Spanish).

Learning anything comes down to two things: practice and performance.

Most of my time was spent playing in the school orchestra class or performing in symphony concerts. Both gave me some anxious excitement. I didn’t want to mess up in front of my classmates or parents or community. At the same time, I wanted to be good enough that people would notice. Luckily, I had some natural aptitude.

I was first chair and consistently making regional orchestra, but if I wanted to aim any higher, I’d need to practice outside of school. My teacher recommended taking private lessons, and I acquiesced. Once a week, I’d go to Ms. Grana…