The Aesthetic Is The Art Now.

Owning an aesthetic is owning influence is owning culture, and it's the future.

Culture is won through aesthetics, and authoring an iconic aesthetic—creating, coining, and embedding it in culture—may be one of the last defining acts of human creativity. Aesthetics shape everything, from creation and consumption to art, science, technology, business, & politics. And in a modern, increasingly AI-native world, the ‘aesthetic’ is the art—it is the unit of cultural currency and the infrastructure. (P.S. See the foonotes for my distinction between taste & aesthetics.)

Note: I wrote this essay before the now infamous ‘Studio Ghibli’ meme surge that took over Twitter / X on the heels of OpenAI announcing it’s latest model 4o’s image generation update. I’ve been pondering this topic ever since the web3 art wave and the emergence of generative AI tools for creativity. I write with conviction, yet it’s rare for such emphatic validation in such a short time—I’ll take it. I may write a short part 2.

Singular masterpieces no longer define culture—aesthetic frameworks do.

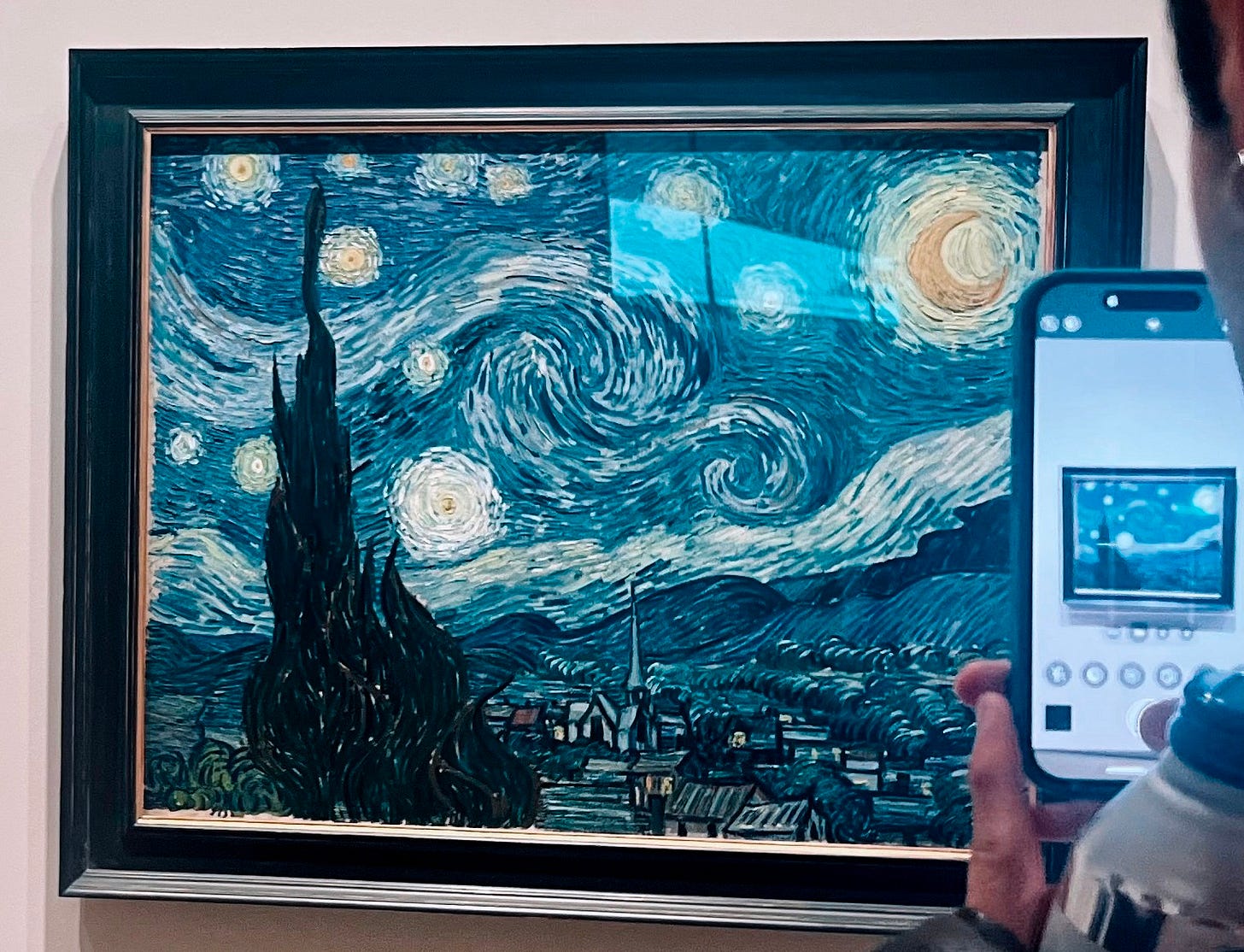

Last fall, I visited the Museum of Modern Art—five floors of mostly unfamiliar works, punctuated by a few cultural lodestones: The Persistence of Memory, Water Lilies, The Starry Night. As crowds gathered, I wondered: A decade from now, will we still admire masterpieces this way?

If Van Gogh painted The Starry Night today, would it still captivate us the same?

Unlikely, I thought.

Creative production has become too easy, and the churn of attention too fast.1 The swirling brushstrokes, vivid blues and yellows, and dreamlike movement—once radical—might barely register in our minds. We've built an immunity to stunning visuals and singular spectacle.

What we would still ascribe artistry to isn’t so much the painting itself, but the aesthetic it embodies: Post-Impressionism, and Van Gogh’s unique expression of it.

What makes it compelling still isn’t technicality but the story he chose to tell and the way he told it—his vision and taste expressed through a signature aesthetic (across four famous starry sky paintings and his entire body of work).23

Van Gogh’s imprint is on culture is not just his individual works, or the collection of them, it is the aesthetic he created that carries on as a historic piece of artistic infarstructure.

Culture wars are won through aesthetics.

Aesthetic warfare is a battle for cultural currency, where people, ideas, and ideologies compete for dominance. Aesthetic wars are waged through frameworks of visual, sensory, and ideological coherence—or the deliberate rejection of them.

With the speed of narrative churn, this battle has become more overt, pervasive, and central than ever—transcending mediums and industries.4

“Must-have” items once defined fashion, but today’s fragmented landscape of micro-trends are all about aesthetic aura—normcore, stealth wealth, office siren, tradwife—each signaling distinct identity markers. This fragmentation and rapid evolution means that no aesthetic is ever allowed to mature, leaving us craving older aesthetics for their sense of permanence and depth.

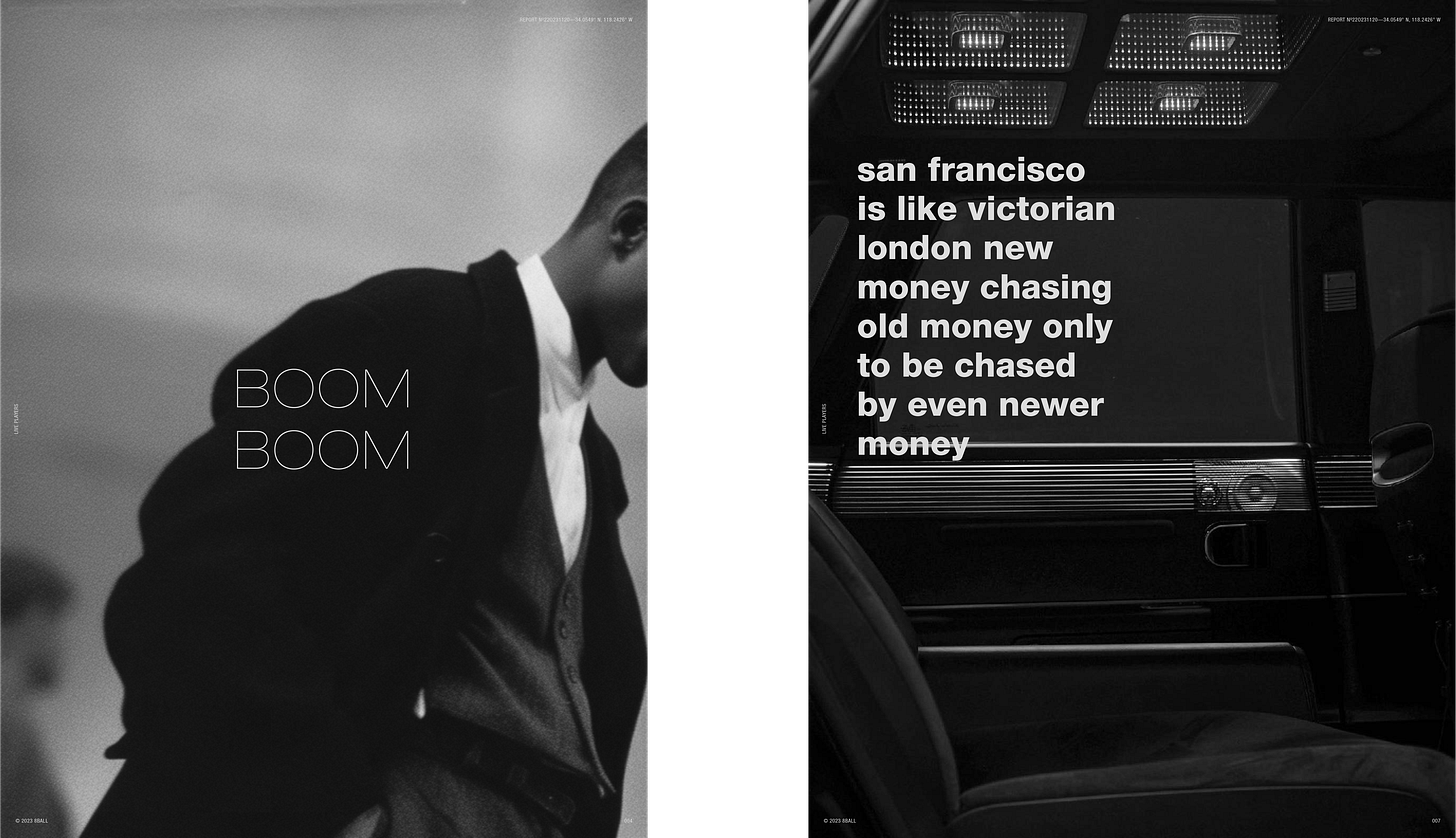

Trendforecaster Sean Monahan explores these aesthetics as ideological frames:

“The eighties archival look that defines the boom boom aesthetic is maximalist in its appetites. Its work hard, play hard ethos presumes an abundance agenda—money earned working funds consumption while playing. After a decade of executives dressing like interns (normcore), touting anti-growth platitudes (degrowth), and smartphones dissolving work/life boundaries, is it any wonder the youth find inspiration in the glamour of the past?”

In film, Christopher Nolan and Wes Anderson embed their distinct aesthetic sensibilities into their own cinematic worlds. Modern art relies heavily on aesthetic ecosystems too: Banksy’s mythology, NFT collections like Bored Apes and Doodles. Their power isn’t in any single image. It is in their distinct aesthetic worlds.

The best companies, products, and teams leverage signature aesthetics as both brand and strategic advantage. These aesthetics shape what they build, how they operate, and create gravitational pull for customers and investors alike.

The ever beloved example from L.M. Sacasas:

“Apple’s success lay not only in its innovation, but also in its aesthetic. The heart is not so pragmatic that it loves what merely works. It loves beauty, and Jobs seems to have known that the consumer would flock to beautifully designed products. The beauty, of course, is of a certain character — minimalist, functional, clean — but it is a recognizable and appealing aesthetic.”

The political battlefield is no different.

The fight between ‘left’ and ‘right’ has played out through aesthetic warfare as much as ideology, or anything else. Fashion matters (see ‘tradwife’ dresses and the strategic implications of Tim Walz wearing plaid flannel). “Woke” has become a banner of the left and weaponized by the right. “Make America Great Again” isn’t just a slogan but a coined aesthetic—a rally cry for patriotic, regressive nostalgia.

We live in a two-aesthetic democracy; a third has yet to break through.

Who authors the aesthetic, and who owns it?

The expansive act of creating, coining, and embedding a new aesthetic into culture is what I call “aesthetic authorship.”

Today, aesthetic authorship is open-source. Where once only the elite artistic class codified aesthetics, now anyone can try (and they are). Some will define an original aesthetic, others will reference it, and still others will copy. An example: Linear’s now-famous aesthetic has been aggressively copied.

Legal battles have even emerged over aesthetic ownership. Consider the dispute over who coined the “sad beige” aesthetic on social media (TikTok and Instagram are literal aesthetic battlegrounds).

Aesthetics are the modern units of cultural currency—stores of value and instruments of power, capable of appreciating and being monetized at scale. Owning an aesthetic is owning influence.5

Every aesthetic has its own language too. The right coined word or phrase doesn’t just describe something—it makes it easier to think or feel a certain way, to align with an identity or worldview.6

So we now ask, straight-faced, “Can you copyright a vibe?” It may seem trivial, but it’s quite prescient.

Art requires faith that the creator has something to say (and AI cannot speak).

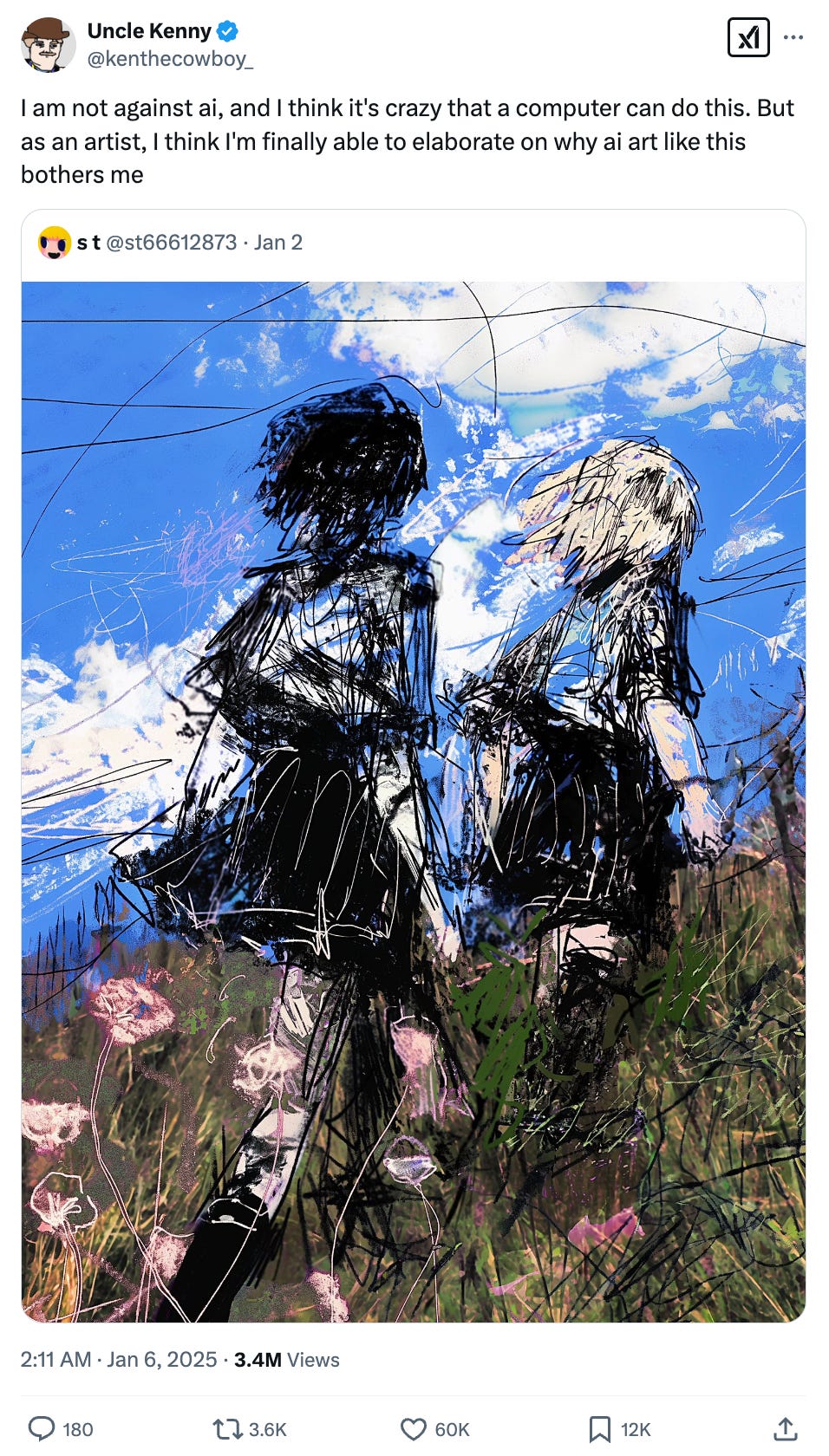

The digital age has brought creative abundance, and AI accelerates this shift. If machines can execute any artistic technique flawlessly, what’s left for humans? AI can generate aesthetics, but can it truly author them?

Take MacbaconAI, an AI artist who posts a steady stream of technofuturist images on Twitter / X under their self-titled style: “New Era Aesthetic.” Their art isn’t about hand-drawn lines but about orchestrating a tool stack: Midjourney, Leonardo, Photoshop, Lightroom. I’d argue their success lies not in any single image, but in the inspiring aesthetic vision they’ve brought to life.

Or consider the AI-generated painting of two girls running in a field that recently went viral. My favorite comment: “I thought this was human-made wtf. WHY IS THERE SOUL IN THIS?” Another argued that AI art like this lacks intent—that it feels deep until you look closer and find nothing. I tend to agree.

Art requires faith that the creator has something to say (and AI cannot speak).

A single AI-generated work, no matter how striking, struggles to convey intent and meaning. But a cohesive body of work—one bound by a human author and their owned, coined, or simply identifiable aesthetic—perhaps can.

We will always seek the human fingerprint—not just the how, but the who and why.

AI will elevate conceptual brilliance, further intensifying aesthetic warfare. (Writers take note.)

I’ll talk about this in terms of writing since I’m immersed in its process:

There’s merit to the quasi-moral stance against assisted writing—and to the cognitive discipline that writing without it requires. Writing is thinking, yes. But creativity in writing isn’t just about words. It’s as much about big-picture storytelling. Venkatesh Rao’s no-airs thoughts on writing with AI resonate:

“AI is great at writing, and even good at the entire pyramid of execution agency — except for the very tip of agency which is actually making creative decisions about what’s worth writing at all and why, and what to prioritize/emphasize for a given purpose. This is almost the essence of writing.”

I’m already of the mindset that most people don’t read every word of an essay anymore; they care more about the 10,000-foot view and a few striking quotes.

With AI tools producing polished prose and argument at scale, what will matter most is an idea wrapped in an aesthetic that asserts itself as special—and human. Writing’s value will lie in conceptual brilliance—where the quality of ideas, world-building, narrative architecture, and aesthetic authorship (an expression of someone’s lived experience, values, and taste)—matter far more than individual words.7

Authoring an iconic aesthetic—creating, coining, and embedding it in culture—may be one of the last defining acts of human creativity.

In the era of infinite creation and consumption, it’s not the technicality of individual works but the authorship of aesthetic frameworks through them that matters. Authoring an iconic aesthetic—creating, coining, and embedding it in culture—may be one of the last defining acts of human creativity. The aesthetic is the art now. The aesthetic is the infrastructure, too. 8

Aesthetics scale—they’re adaptable, reusable, and propagate beyond their origins, acting as powerful cultural infrastructure. The power of an aesthetic today is that it holds inherent viral potential. With the acceleration of creative tools and networks, an aesthetic can spread—in earnest, in memes, or both—in 24 hours or less. “Copying” or “remixing” aesthetics is just as easy now.

What does this mean for brilliant artists of the past—like Van Gogh—whose aesthetics will live on yet propagate beyond their control? What will it mean for the artists of today who still seek to create with depth and meaning and not just for memetic potential? How do we judge and value, culturally and financially, the contributions of these aesthetic authors? If attention is all you need, and attribution is sorted out to any degree, might it be the ultimate reward?

How this impacts meaning and longevity is perhaps collateral damage, or an opportunity for caretakers of culture to rally around. Some may resist, embracing anti-aesthetic creation and consumption—fractured, erratic, ephemeral. Others may retreat to singular, unique masterpieces in defiance. Anonymity and pseudonymity, however resistant, have become aesthetics too—proving that culture is always defined, if not by choice, then by contrast.

To win the world, you must win the culture war, and the culture war is a battle of aesthetics. And in an AI-driven world, aesthetic authorship may be one of the last true assertions of human creativity. So now, more than ever, we must author the aesthetics that align with our values—that we want to shape our culture.

If you enjoyed this essay, like and share with a friend or community that might too, or let’s chat in the comments. If you’re new to my writing, here’s a list of my top essays.

At this point, we should split “culture” into layers—a surface layer and a deep layer. Most of what’s created, consumed, and perceived as culturally relevant now is just surface culture. This is my theory on why we think culture is “stuck” and every movie/tv show and style is a reboot or throwback—because deep culture is largely in the past.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how a single word can encapsulate a universe of meaning. Last year, I wrote about taste as a final frontier, only to be swiftly reminded how words that enter the discourse accumulate baggage and become unwieldy. That said, I wanted to explore something adjacent: aesthetics.

Aesthetics is sensory form shaped by principles—encompassing the underlying logic behind what we may find visually, emotionally, or intellectually compelling. Taste, on the other hand, is how we personally respond to the logic—what we like.

Today, the timeline between creation and classification has collapsed. Monet’s Impressionism, for instance, wasn’t coined by him but by critics who mocked his work as an "impression,” not a finished painting. But creators no longer wait for history to classify their work. They’re urged to frame and name their work now.

There are many mediums I haven’t covered here, but aesthetics still reign. Music is deeply rooted in aesthetic philosophy and frameworks—often more scientific than other creative fields. Even sports carry a distinct aesthetic, from the style of play to fashion, media, and the culture surrounding it. Interior design is all aesthetic trends.

Any aesthetic is only as moral as its use. The power and peril of aesthetic frameworks lie in their ability to either foster authentic self-expression or reduce identity to mere signaling. Not surprisingly then, superficial aesthetic alignment commodifies identity—and at times, even personal struggles—offering only surface-level meaning, or worse. A now-classic take by Rayne Fisher-Quann:

“It’s become very common for women online to express their identities through an artfully curated list of the things they consume, or aspire to consume ... The aesthetics of consumption have, in turn, become a conduit to make the self more easily consumable: your existence as a Type of Girl has almost nothing to do with whether you actually read Joan Didion or wear Miu Miu, and everything to do with whether you want to be seen as the type of person who would.”

Coining terms that enter culture has always held value. Yet, sometimes, naming something too soon dilutes its power. In fashion, aesthetics often build through aura, association, or embodiment rather than explicit definition. By the time an aesthetic gets a name, it can mark the shift from cultural creation to mainstream adoption (making it less cool). But whether named or not, aesthetics gain traction through authors and acolytes—figures who define, shape, and embed them into culture.

Art has arguably always been judged this way. But it’s not just an advantage now, it’s existential. The details have become secondary. Artistry has zoomed out.

Perhaps this is how it always was, but the technical masterpiece that accompanies the iconic aesthetic simply matters far less now.

Brilliant. Something I've thought about as well, that individual art pieces (digitally reproduced) hath become a commodity. The art itself now isn't what it used to be, but it's now in the decisive overall vision and aesthetic of a brand; in a certain feel, perhaps? Is that what you mean with "artistry has zoomed out"? Thanks for writing all of this out.

This essay feels eerily prescient now that this Ghiblification craze is in full swing