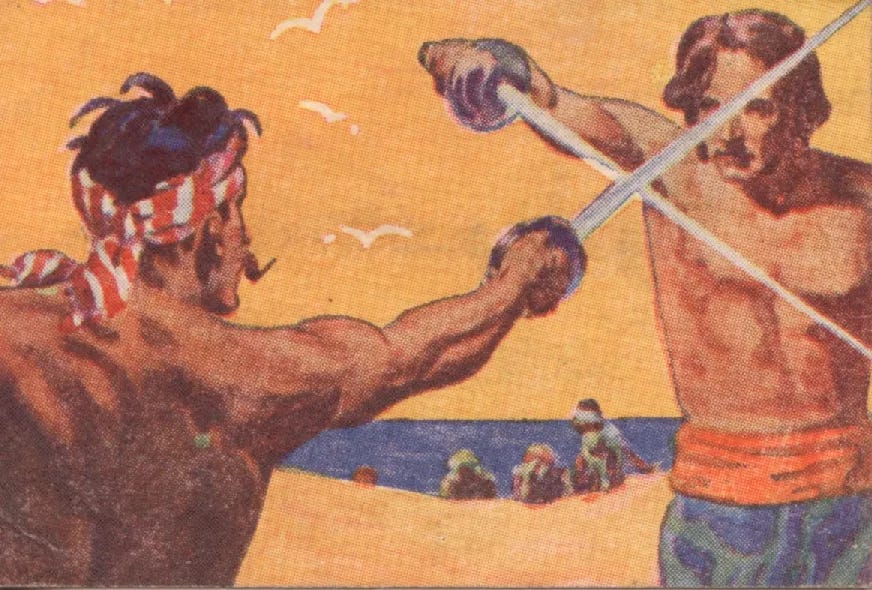

Invisible Duels

You didn’t agree to this duel, but it’s happening.

This is an essay about a deeply human tendency and unpleasant truth that exists in every competitive, ambitious community (and in all communities to a degree). It’s the struggle behind the pure “positive-sum” aspiration. This essay is an attempt at “saying the quiet part out loud” to ideally contribute to greater self-understanding and the greater good.